- What is electricity?

- Resistance, Conductance & Ohms Law

- Practical Resistors

- Power and Joules Law

- Maximum Power Transfer Theorem

- Series Resistors and Voltage Dividers

- Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL)

- Parallel Resistors and Current Dividers

- Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL)

- Δ to Y Network Conversion

- Y to Δ Network Conversion

- Voltage and Current Sources

- Thevenin’s Theorem

- Norton’s Theorem

- Millman’s Theorem

- Superposition Theorem

- Mesh Current Analysis

- Nodal Analysis

- Capacitance

- Series & Parallel Capacitors

- Practical Capacitors

- Inductors

- Series & Parallel Inductors

- Practical Inductors

Resistance

Resistance, as it’s name suggests, is the property of resisting the flow of electricity.

In our water analogy it is the cross sectional area of the pipe along with how smooth, straight and long the inside of the pipe is that restricts the flow. In the case of our free electrons flowing through the atoms of a material it is how tightly the electrons are bound to their atom, how tightly packed the atoms are, the cross sectional area and length of the path through the material that restricts the flow. This resistance (symbol Ω) has been given, for a change, the intuitive designation of R in electronics. We’ll look at the definition of Ohms more closely in a few minutes.

Or at least that’s the case for a steady constant flow in one direction (direct current – DC). Things are a lot more complicated if the current is changing directions (alternating current – AC) or amplitude. Even for the short transient when DC flow starts and again when it stops. However, that is a topic for later. For now we’ll stick with the aspects that are important for DC steady state electricity flow.

Conductance

Conductance is a complementary measurement to resistance and is measured in siemens (symbol S) and given the designation of G. Note that it used to be measured in a unit called the mho having the symbol (℧). As you will see in a moment, it is no coincidence that both the old name and symbol are the upside down ohms equivalents.

Where the measure of resistance (R) determines the reluctance of a material to pass an electric field. The measure of conductance (G) determines the ease with which an electric field can pass. They are opposite (inverse) concepts and so, unsurprisingly perhaps, conductance is just the reciprocal of resistance.

\(G = \frac{1}{R}\)

This may seem like a measurement for measurements sake, but there are a few circumstances when it makes more sense to consider conductance rather than resistance. An example, as we will see in a later topic, would be in current divider circuits.

Ohms Law

Ohm’s law states that:

For a linear circuit in a steady DC state, the voltage across two points is directly proportional to the current running between the two points.

Which, in simple terms, means that the voltage across a component (or sub-circuit) is directly determined by the current passing through the component (or sub-circuit) multiplied by some constant. The constant being the resistance between the two points.

In symbolic form this is expressed as one of the following (depending upon which is the variable of interest):

If we are trying to find the potential difference in volts:

\(V = I.R\\\)Or, if we are trying to find the current in amps:

\(I=\frac{V}{R}\\\)Or, if we are trying to find the resistance in ohms:

\(R=\frac{V}{I}\)

The above formulae are so critically important to almost everything that you may ever want to do in electronics that they should be burned in to memory. That said, you only need to memorise one of the forms and all of the others can be quickly derived by rearranging that one equation1

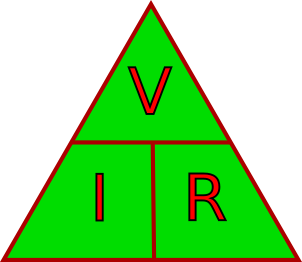

As an alternative, many people find that an aide-mémoire such as the one below helpful. Just place a thumb over the value of interest, and the remaining letters show how to obtain that value. For example, to find the voltage cover V and what remains is I x R. Alternatively to find the current, cover I and what remains is V over R, etc.