- What is electricity?

- Resistance, Conductance & Ohms Law

- Practical Resistors

- Power and Joules Law

- Maximum Power Transfer Theorem

- Series Resistors and Voltage Dividers

- Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL)

- Parallel Resistors and Current Dividers

- Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL)

- Δ to Y Network Conversion

- Y to Δ Network Conversion

- Voltage and Current Sources

- Thevenin’s Theorem

- Norton’s Theorem

- Millman’s Theorem

- Superposition Theorem

- Mesh Current Analysis

- Nodal Analysis

- Capacitance

- Series & Parallel Capacitors

- Practical Capacitors

- Inductors

- Series & Parallel Inductors

- Practical Inductors

Charge and Volts

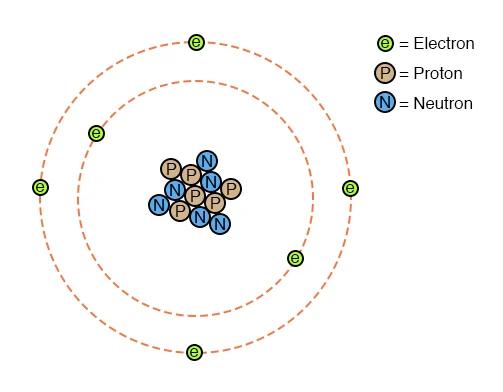

To avoid a long excursion into fundamental physics and the history of it’s discovery we will accept on faith two fundamental facts:

- The basic building blocks of all material things are atoms;

- Ignoring all the exotic particles, atoms are comprised of three fundamental particles:

- Protons

- Neutrons

- Electrons

Before we go any further. Yes I am aware that this is not really how atoms look, but it is the classic model and it works for my purposes here.

Of these three items, the nucleus of an atom is comprised of one or more Protons and zero or more Neutrons. These are very tightly bound to the atom and are very difficult to remove or add.

Electrons on the other hand, are much less tightly bound. They have a lot more freedom of movement and can be knocked out of position (even out of the atom completely) by far less energy than would be needed to dislodge either a proton or a neutron. The atom still retains it’s original elemental identity after the loss of an electron (though technically it is now an ion, not and atom), but a very important imbalance occurs.

Electrons and protons are attracted to each other, while electrons repel each other, as do protons. Due to this attraction/repulsion effect, electrons and protons are considered to carry opposite electrical charges. Electrons carry a negative charge and protons an equal and opposite positive charge. In this way, while the number of electrons match the number of protons in an atom, the atom exhibits a net zero charge.

It is very important to note however, that charge is not the same thing as energy. Charge is measured in units of coulombs (symbol C), and rather confusingly is given the designation of Q in electronics. While energy is measured in units of joules (symbol J).

So the question is: If a charge is not itself energy, where is the energy and how is it stored by the charge? The answer is complicated, but the short answer is that all charges produce an electric field, and moving charges also produce a magnetic field. In combination these two fields store the energy and ultimately enable power transfer. However, to explain that further requires explanations of Maxwell’s equations, Poynter Vectors and the Lorenz force. Unfortunately Alice is not here to guide us at the moment so we will go down that particular rabbit hole on another day.

What we can safely say however, is that the relationship between charge and energy is the amount of work that it would take to move a charge between two points. This is the Potential Difference which is measured in a volts (symbol V).

Backtracking slightly. A coulomb is a very large unit, but the amount of charge on a single electron is very tiny, and is approximately:

Charge on an electron = 1.602 x 10-19 coulombsThis is called the elementary charge and is given the symbol e. So we can say that a proton carries a charge of +e and an electron carries a charge of -e.

Volts on the other hand, being a measure of potential work to be done, are a measure of joules per coulomb. In fact the voltage difference (or Potential Difference) between two points is the number of joules that it would take to move one coulomb of charge between those two points.

\(1.volt = \frac{1.joule}{1.coulomb}\) So we can say that:

\(V = \frac{J}{Q}\)

Water and it’s flow is often used as an analogy when explaining various aspects of electricity. In that scenario voltage can be thought of as being the pressure of the electricity. It is not important to remember the formula given above. It is only shown because it is useful later in showing how other important formulae are related and derived.

Static electricity?

Under certain conditions Electrons can be dislodged from an atom by mechanical movement of one object against another. The result of which is that one of the two objects looses electrons and the other object gains those lost electrons. Thus one of the objects attains an overall positive charge and the other an overall negative charge. Since the transferred electrons stay in their new location, it is known as a static charge and hence we have static electricity.

This build up of static charge can be huge, in the order of hundreds (even thousands) of volts. However, it is relatively safe (to humans, but not electronic components) because when it is discharged there is very little energy to convert in to power. We’ll get on to how electrical energy is carried later (note that I said carried and NOT generated – energy can only be transformed and not created [conservation of energy and all that]).

Note that electrons of different atomic elements have differing amounts of freedom of movement.

Insulators

In some materials such as glass, ceramic and most plastics, the outer electrons have very little freedom of movement. Although external forces, such as mechanical rubbing, can force a few electrons to transfer to another material, they do not easily move between atoms, even of the same material. These materials are known as insulators.

Conductors

In other materials, such as metals, the outermost shell of electrons for the atom are so loosely bound (and the atoms so tightly packed together) that those outer electrons can move relatively freely not only within the atom, but between different atoms in the same material, influenced by nothing more than room-temperature heat energy. As these electrons are fairly free to move around in the space between atoms they are referred to as free electrons. The materials that exhibit this behaviour are known as conductors.

Electron Flow / Current Flow

The normal motion of free electrons (and hence their charge) in a conductor is random and the movement has no particular direction or speed. However, they can be externally coerced into a coordinated movement and direction by applying a potential difference (voltage) between two points. In contrast to static electricity you might expect this uniform movement of charge to be known as dynamic electricity, unfortunately it isn’t. It is simply known as electron drift or just plain electricity.

As an aside, you may be wondering how fast these electrons flow, and the answer may surprise you. Contrary to popular expectation, they do not flow at (or anywhere near) the speed of light. The drift velocity is proportional to the current flowing (and any external electric field). The drift velocity is in the order of just 1 mm per second (compared to their velocity due to thermal energy which is the order of 1 million metres per second) and is in opposition to the electric field. In fact, in a copper wire with a diameter of 2 mm, carrying 1 amp of current. The electrons have a drift speed in the region of just 8 cm per minute!

Anyhow, back on topic. Remember that an electron carries a charge, and so the flow of electrons also represents a flow of charge which is known as the current, and this is measured in amperes (symbol A), or more commonly just called amps. Once again, it rather confusingly has been given the designation I in electronics. The important take away here is that amperes are a measure of the rate of flow of charge, and hence carries a time component (this will be important later when we come to power).

\(1.ampere = \frac{1.coulomb}{1.second}\) so we can say

\(I = \frac{Q}{s}\)

Continuing with the common analogy between electricity and water. If voltage is the pressure, then amperes are the rate of flow (current) of the water.

Hi Ian

I have read your article on electricity and as interesting as it was I found it a little hard going. This may be because it is a while since I have studied in detail.

Regards

Neil

Thanks Neil. Though I suspect that it has more to do with my lack of writing skills than any failing on your part.

This was my first attempt at writing my personal revision notes in a format for other people to read. I am still trying to find my feet with determining how deep down the rabbit hole to go with the detail. Hopefully as the number of posts increases, then so too will my ability to write more clearly and succinctly.

Also, I have quickly discovered that just because I know something, doesn’t necessarily mean that I can easily verbalise what I know.